Humanity’s earliest recorded kiss adds new twist to the history of locking lips

SMM ALIPAYUS Feb 13, 2024 World

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

“The meeting of lips is the most perfect, the most divine sensation given to human beings, the supreme limit of happiness.”

So wrote the 19th century French author Guy de Maupassant in his 1882 short story, “The Kiss.” He wasn’t alone in his flowery thoughts about kissing. Romantic kisses have long been celebrated in songs, poems and stories, commemorated in art and film.

No one knows for sure when humans first figured out that mouth-to-mouth contact could be used for romance and erotic pleasure, but scientists reported in May 2023 that people were locking lips at least 4,500 years ago. The findings, published in the journal Science, pushed back the history of the practice by about 1,000 years.

“Kissing has been practiced much longer than perhaps a lot of us realized, or at least had thought about,” said lead study author Dr. Troels Pank Arbøll, an assistant professor of Assyriology — the study of Assyria and the rest of Mesopotamia — at the University of Copenhagen.

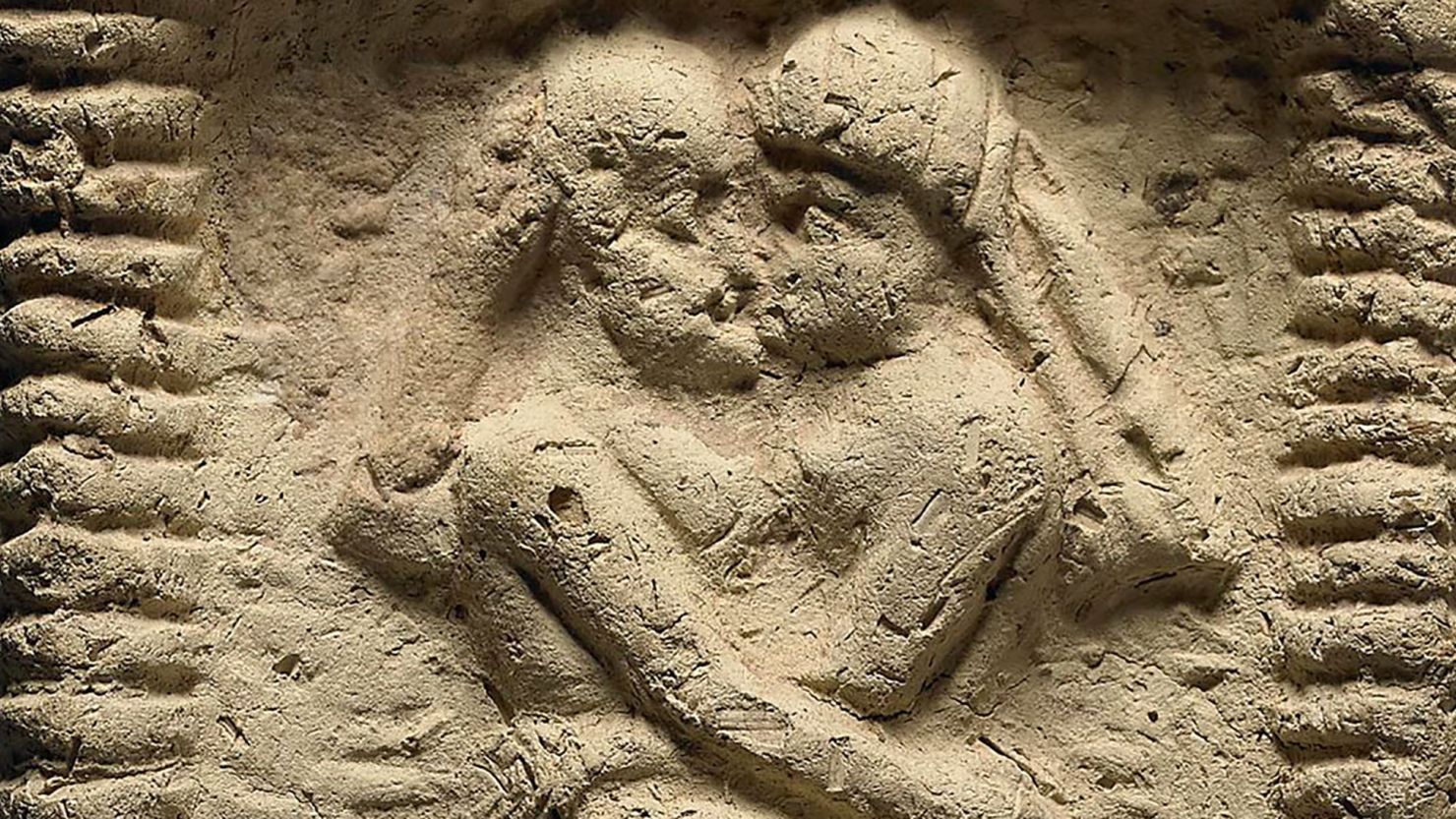

Thousands of clay tablets from Mesopotamia survive to the present; their references to kissing shed light on romantic intimacy in the ancient world, the researchers reported.

Related article 6 historical mysteries that scientists finally cracked in 2023 — and one they didn’t

“This fascinating case study adds to a growing body of scientific research on romantic/sexual kissing, and helps us understand kissing’s origins in human social behavior and in intimate life specifically,” said evolutionary biologist Dr. Justin R. Garcia, a professor of gender studies at Indiana University in Bloomington. Garcia, who investigates the culture and evolution of human intimacy at the Kinsey Institute, was not involved in the research.

“Romantic and sexual behavior experiences are part of larger patterns of human social behavior,” Garcia told CNN in an email. “Understanding how these behaviors express themselves, change, and evolve helps us better understand who we are today.”

When de Maupassant wrote his heartfelt descriptions of loving kisses, he probably wasn’t thinking too hard about how kissing arose in the first place amid civilizations of the past. But the origins of this “most divine sensation” are deeply rooted in human history and evolution, and there is likely much about its role and significance in ancient cultures that is yet to be discovered, the study authors wrote.

Passionate kisses

Previously, the oldest recorded evidence of kissing was attributed to the Vedas, a group of Indian scriptural texts that date back to around 1500 BC and are foundational to the Hindu religion. One of the volumes, the Rig Veda, describes people touching their lips together. Erotic kissing was also featured in great detail in another ancient Indian text: the Kama Sutra, a guide to sexual pleasure dating to the third century AD. Modern scholars therefore concluded that romantic kisses likely originated in India.

But among Assyriologists, it was widely known that clay tablets from the region mentioned kissing even earlier than it was described in India, Arbøll told CNN. However, outside of highly specialized academic circles, few knew that such evidence existed, he added. In the study, Arbøll and coauthor Dr. Sophie Lund Rasmussen, a research fellow in the department of biology at Oxford University in the UK, wrote of kisses inscribed in Mesopotamian tablets dating to 2500 BC.

“As an Assyriologist, I study cuneiform writing,” Arbøll said. Cuneiform, in which characters are pressed into tablets using cut triangular reeds, was invented around 3200 BC. Early cuneiform was used by scribes for bookkeeping, Arbøll explained. But around 2600 BC — perhaps even earlier — people began recording stories about their gods.

Related article Meet the animals with love lives more complicated than yours

“In one of these myths, we get this description that these gods had intercourse and then kissed,” he said. “That’s clear evidence of sexual romantic kissing.”

Within a few centuries, writing had become more widespread across Mesopotamia. With that came more records of daily life, with mentions of kisses traded by married couples and by unmarried people as an expression of desire.

Some examples cautioned about the perils of kissing; to kiss a priestess sworn to a form of celibacy “was believed to deprive the kisser of the ability to speak,” according to the study. Another prohibition addressed the impropriety of kissing in the street; that this warning had to be made at all, hinted that kissing was “a very everyday sort of action,” albeit one that was preferably practiced in private, Arbøll said.

Across thousands of cuneiform tablets kissing isn’t the most mentioned topic, “but it is attested regularly,” he said.

Don’t talk, just kiss

Humans aren’t the only animals that kiss — so do our closest primate relatives. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) trade kisses as greetings. For bonobos (Pan paniscus), kissing is part of their very frequent sex play; they copulate face-to-face and often engage in “intense tongue-kissing,” wrote primatologist Frans B.M. De Waal, a behavioral biologist at Emory University in Atlanta.

It’s possible that romantic kissing evolved in primates as a way to evaluate fitness in a potential mate, “through chemical cues communicated in saliva or breath,” Arbøll and Rasmussen wrote.

But kissing isn’t all sociability, fun and pleasure. One less enjoyable side effect of kissing in humans is the spread of infectious disease. Another study, authored in July 2022 by more than two dozen researchers from institutions in Europe, the UK and Russia, stated that the rapid rise of a lineage of the herpes simplex virus HSV-1 in Europe about 5,000 years ago, was “potentially linked to the introduction of new cultural practices such as the advent of sexual-romantic kissing,” following waves of migration into Europe from the Eurasian grasslands.

But Arbøll and Rasmussen suspected that romantic kissing became accepted in Bronze Age Europe, and not because of migration alone. It’s more likely, they wrote, that the practice of kissing was already at least passingly familiar to people in Europe because it was common in Mesopotamia — and possibly in other parts of the ancient world — and wasn’t just restricted to India.

“It must have been known in a lot of ancient cultures,” Arbøll said. “Not necessarily practiced, but at least known.”

Kissing then and now

Unlike the kisses shared between parents and children, which are thought to be “ubiquitous among humans across time and geography,” romantic kisses are not common everywhere. Even today, many cultures shun romantic kissing, Arbøll and Rasmussen reported.

In a September 2015 study coauthored by Garcia, researchers surveyed 168 modern cultures worldwide, finding that only 46% of those societies practiced kissing that was sexual or romantic. Such kissing, the authors reported, was far less common in foraging communities, and was more likely to be found in societies that had distinct social classes, “with more complex societies being more likely to kiss in this manner.”

While Arbøll and Rasmussen’s study suggests that romantic kissing wasn’t unusual in ancient Mesopotamia, the authors point out that there were still taboos about who could kiss and where they could do it — and that romantic kissing was far from a universal experience across all cultures.

Related article Stone Age megastructure found submerged in the Baltic Sea wasn’t formed by nature, scientists say

“This article is an important reminder that widespread kissing we see represented all around us in western society today was not always, and is still not always, a part of everyone’s displays of intimacy,” Garcia said.

It’s also possible that if kissing in the ancient world was more widely distributed than once thought, it was “perhaps more universal than in modern times,” Arbøll added. “It opens some questions that are interesting for future research.”

Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American and How It Works magazine.